The following five suggestions are based on my experience and are meant to keep both you and your horse safe. This also creates an optimal working environment for a successful and enjoyable experience. Enjoy your horses, Jim.

1. Where to work.

Ideally, I like to work on a horse in a stall. There are a number of reasons for this. First of all, I can step back from the horse to see what he has to say without him running off into the sunset. Stepping back and out of their immediate space makes many horses that more comfortable, and they will release more readily. Secondly, it gives the horse the room to move around (fidget) if he needs to while I continue working on him. In a sense, I am “yielding” to him as I continue my work. Another reason a stall is good to work in, is if I need the horse to stand still I can position him against the stall walls where I want him. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, you and the horse’s safety come first. You need to have the ability to leave the stall quickly and easily if necessary. The nature of this work will, in most cases, keep the horse happy and “with” you.

2. Keeping a connection with the horse.

When working on a new horse you may like to have another person nearby or holding the horse’s lead rope. If you have an assistant in the stall, it is important that they stand back away from the horse and not interact with him in ways that will interfere with your ability to read his responses. This can include petting, rubbing ears, eyes or nose, or any other behavior your handler might find tempting. Your connection with the horse is what makes this work, and your ability to watch the horse’s movement and responses to your touch is an important part of the work.

Unfortunately, now is not the time for treats! Food is one thing that interferes with this process of “reading” and following the horse’s responses and keeping him connected to you. So, be sure to remove food or any other distraction from the stall.

3. Using a halter and holding or tying the horse.

I prefer not to hold or tie the horse unless the horse won’t stay still for the work. If you prefer to have a handler or you tie him, it is important that he is able to move his head and body as freely as possible without interfering with your ability to do your job.

If you decide to tie a horse you are unfamiliar with, or one that might be likely to pull back, then tie him in a way so that the rope will come loose easily, and not break the halter, hurt the horse, or disassemble the stall. Tie the lead rope to a piece of baling twine, or wrap it loosely around a bar or through the stall bars in such a way so it will pull free when tension is applied. This saves some time when trying to get a horse calmed down again after a pulling-back episode. If you are working alone and don’t feel the need to tie the horse, you can drape the lead over the horse’s neck as you are working. With time, you may become comfortable working on the horse without a lead rope. He is, after all, in a stall and can’t wander too far.

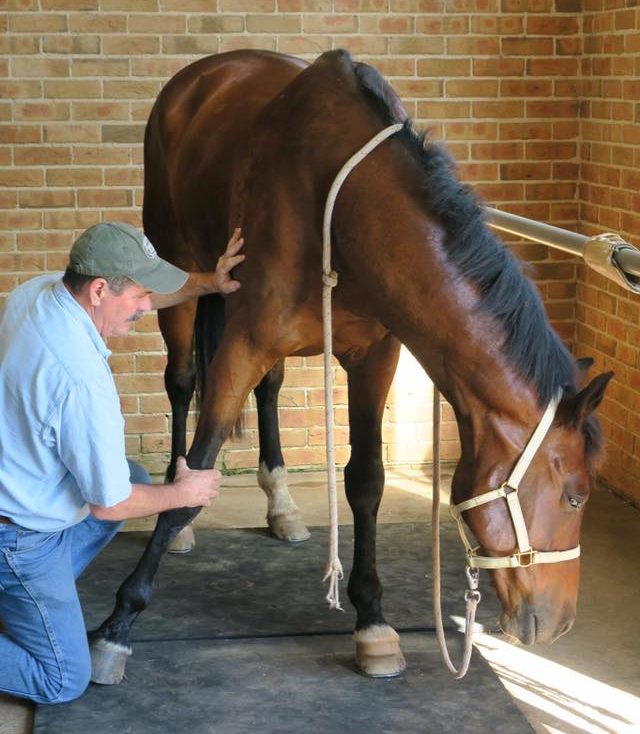

4. Techniques that involve handling the hind legs.

It is important to be aware of the horse’s state of mind, especially at first, until the horse is used to you. (Of course, this applies to the front end too, because a horse can act unpredictably at both ends! And always, keep an eye on the horse’s ears whenever you first touch a horse that could be sore.)

This sense of awareness should become second nature in your handling of the horse; as it goes along with the sense of “feel” that you will be developing in the days to come. However, when starting out, it is important to be consciously aware of what you are doing and the effect you are having on the horse.

When you get to the hind end be aware the horse might be sore in the sacral area, gluteal muscles, hamstrings, groin, or abdominals.You would have already done the Bladder Meridian Technique, so continue to go lightly over some of these areas, and his response then should have let you know if he has tension or pain there. In fact, you may have already helped the horse to release some of this tension. However, you won’t have covered the groin, abdomen, or between-the-legs areas, so it pays to be careful and keep an eye on his ears for signs of distress when first touching him anywhere he might be hurting.

The illustrations in Part Two of the Beyond Horse Massage Book show you how to best position your body in order to stay safe around the horse. When handling the legs be sure that the horse has room to move away from you rather than over you should something spook him. In my experience, 95 out of 100 horses would rather go around you if they have the option. It’s best to leave a pathway to accommodate them.

5. Quiet time and frame of mind.

Pick a quiet time for your bodywork session. Feeding or anxious high traffic times in the barn will make your work less effective (and may wear you out). Assess your own frame of mind. Be as relaxed and calm as possible. Remember to breathe!

When you enter the stall, don’t go straight for the horse’s head. Stop for just a second and stand in a relaxed manner, maybe shift your weight from one leg to the other like a calm horse does, then walk (I like the word “amble”) easily up to the horse’s shoulder and let him know you’re not there to jab him with a needle or something. Then ask him (using the principle of non-resistance) to step somewhere: maybe away from the wall to the center of the stall, or back away from you if he is pushing into your space—anywhere to get him to move his feet for you. Once you take the time to watch you’ll notice that when you first ask him to do something, such as move his feet for you, and he yields and you soften, he will let out a sigh of relaxation, or lick and chew, or blink. Again, this gets his nervous system into the yielding or “following” mode, rather than the bracing or “leading” mode.

Learn about The Masterson Method Techniques and much more in our Beyond Horse Massage Book.

4th photo courtesy Crissi McDonald.